Ari Hunter is a student with Deakin University’s Master of Cultural Heritage & Museum Studies program. Ari undertook an internship at the Geoffrey Kaye Museum of Anaesthetic History during September and October 2015.

One of the tasks during my internship with the Geoffrey Kaye Museum was to write significance statements. The first one was for a piece of medical equipment known as the Bruck Inhaler.

My initial thoughts were that the object would be significant only for its historical use, and the innovation in design because of the addition of the glass bowl. This looked on the surface to be a straightforward task with a logical, linear progression. It wasn’t. The research was a long journey down a rabbit hole and this whole project was a learning curve in many ways.

It also prompted me to reassess my research methods, learn how to organise these documents, and try to keep myself on task without getting too far into the personal stories of the characters involved.

The object record in the collection database held mostly technical information about the use of the inhaler, and a quick description of its physical state. The record did note ‘L Bruck’ of Sydney as the maker, as marked on the bowl in a flowing script. In the collection record, the maker was listed as ‘Lambert Bruck’.

Initial research pointed me toward a physical understanding of the inhaler, how it was used and what was primarily significant about the design. The piece is historically significant as it signalled a change in the way ether as an anaesthetic was delivered. The Bruck Inhaler is simply a needs based modification of the earlier Clover Inhaler. The addition of a glass bowl eliminated much of the guesswork associated with dosage levels, which in turn improved the patient experience. The idea of social context and patient experience surrounding the modification of anaesthetic equipment also piqued my interest.

My next point of investigation was to discover more about the maker of the object. This opened up a can of worms.

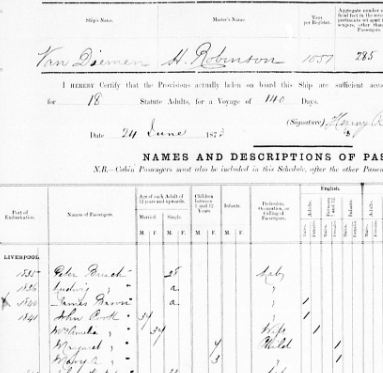

Ludwig Bruck was an immigrant of German decent. This placed him in a precarious position within Australian society around the turn of the century. He arrived in Melbourne, aboard the Van Diemen, in 1873, first living in Melbourne. A rate book from 1881 records Bruck as the owner and occupier of a brick property in Washington Street, Toorak. Towards the end of 1881, he relocated to Sydney and was employed as a manager at the Intercolonial Transfer and Medical Agency Office.

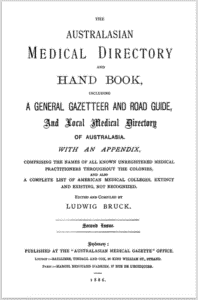

He was also a prominent figure in the medical industry. He started his medical career in Sydney as a Medical Transfer Agent, and later owned a shop at 16 Castlereagh Street, Sydney. This business is listed in the 1903 Register of Firms as a Medical Agent and Importer of Medical Instruments and Books.[1] Bruck was vocal as a journalist and published analyses of medical statistics, as well as the well known Australasian Medical Dictionary and Handbook, which included the “List of Unregistered Medical Practitioners”.[2]

Bruck conducted several public conversations with prominent members of the Australian Natives Association (ANA) through the Sunday News disagreeing with the employment of medical practitioners by the ANA specifically to corroborate their health insurance policies. He was also a stalwart supporter of the Australian arm of the British Medical Association and was the publisher of the first and subsequent editions of The Australian Medical Gazette.

Bruck chose to end his life with a combination of poison and chloroform on 14 August 1915, after being accused of trading with the enemy during World War I. His suicide note stated his horror at leaving his business partner to deal with the tarring of his reputation as the reason for his decision.

Finding that the maker / designer / commissioner of this unassuming object chose to end his life with chloroform was really quite consuming. Finding and reading his suicide note published in the paper was extremely confronting. I wasn’t ready to get that close.

This story imparted the inhaler with a high level of social significance that was never expected. It was at this time the direction of my research changed. My supervisor floated the idea of publication, as this content was not widely known.

More time was spent looking through ships notices for arrival dates, birth records, letters to the editor in Sydney and Melbourne papers, and rent books to find out more about this figure. A picture of Ludwig Bruck started to form, as did evidence of his outspoken views.

The learning points I have taken from this are huge. I know now not to take anything in any collection at face value, as it could really go in any direction. On that note, I need to be more aware about where it does go, as being more open to little clues in the beginning could have saved days of work. And Endnote. This changed my life. The ability to save a PDF export from Trove with all the citation details is incredibly geeky, but so amazing.

A larger version of the Bruck story was published in the ANZCA Bulletin in 2015. The Bulletin has a print run distribution of over 8000. I have a publication credit and the museum has a larger picture of the history of the man and the object.

[1]. NSW Government – State Records. 1903 Register of Firms

[2] Alafaci, A. (2006, October 2006). Bruck, Ludwig. Retrieved November 2015 from Encyclopaedia of Australian Science: http://www.eoas.info/biogs/P004838b.htm

By Ari Hunter

Ari Hunter is a student with Deakin University’s Master of Cultural Heritage & Museum Studies program. Ari undertook an internship at the Geoffrey Kaye Museum of Anaesthetic History during September and October 2015.